If you begin to look for one of the earliest depiction of Krishna and Balarama outside of India, it's hard to imagine that you'd find them on a Greek coin. Surprisingly, it's true!

Agathocles, an overlooked Graeco-Bactrian ruler, left behind stunning coins that today serve as crucial numismatic evidence and reshape our understanding of cultural fusion in antiquity.

The ancient world was a melting pot of cultures, religions, and ideas, and nowhere is this more evident than in the coinage of Graeco-Bactrian King Agathocles. Unlike many rulers whose legacies are chronicled in written records, Agathocles remains an enigmatic figure known primarily through his extensive coinage. Likely a son of Demetrius, he ruled the Paropamisadae—a rugged region bridging Bactria and India—during a period of geopolitical flux.

Bactria was an ancient region located between the Hindu Kush mountains and the Amu Darya River, in what is now Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. From around 600 BCE to 600 CE, it played a key role as a hub for trade between the East and West and was a center for the exchange of proliferating religious, spiritual, intellectual and creative ideas. Though textual records offer little about Agathocles, the ruler of Bactria, his coins serve as a remarkable testament to the cultural and religious interplay between the Greek and Indian worlds.

Archaeologists and numismatists have studied large hoards of Agathocles’ coins, particularly those discovered in modern-day Afghanistan. He was the first Greco-Bactrian ruler to introduce bilingual inscriptions, blending Greek and Brahmi, and also issued coins in Kharoshthi script. These linguistic choices reflect the dynamic cultural fusion of his era, emphasizing his role as a bridge between Greek and Indian traditions.

The Influence of Indian deities within and beyond the Indian subcontinent

The worship of Vasudeva Krishna finds its roots in Mathura, a city long associated with the deity. Interestingly, the Greek ambassador Megasthenes mentions that the Sourasenoi of Mathura worshipped a god he equated with Herakles. Historians now agree that Megasthenes was likely referring to Lord Krishna, drawing parallels between the two mythological figures.

Among Agathocles’ most intriguing coinage are square, die-struck silver coins excavated at Aï-Khanoum, Afghanistan. Weighing between 2.328 and 3.305 grams, these coins resemble the punch-marked currency of the Indian subcontinent. A detailed examination of the figures depicted on these coins, dated between 180 BCE and 170 BCE, reveals fascinating insights.

One figure, holding a plow in his left hand, has been identified as Balarama, also known as Haladhara in Hindu mythology. His right hand holds a pestle or musala, further solidifying his identity. On the reverse side, another figure is depicted holding a large six-spoked wheel, recognized as the Sudarshana Chakra, a weapon closely associated with Krishna. The inscriptions on these coins are bilingual—Greek on the obverse and Prakrit in Brahmi script on the reverse—signifying Agathocles’ deliberate engagement with both Greek and Indian audiences.

Beyond Krishna and Balarama, Agathocles’ coins also depict Goddess Subhadra, their sister. According to the Harivamsha and Mahabharata, Subhadra was born to Vasudeva and Rohini, later marrying Arjuna. Her presence on these coins further underscores the Indo-Bactrian ruler’s engagement with Vaishnav traditions.

Archaeological Corroboration from Chilas, Kashmir

Additional archaeological evidence supporting the worship of Balarama and Krishna beyond Mathura comes from Chilas, Kashmir. Here, rock carvings along a major trade route depict two male figures wielding a plow and a wheel. These figures, clad in open coats reminiscent of Kushan attire, bear a striking resemblance to those on Agathocles’ coins. Inscriptions in Kharoshthi found in the region further substantiate their identification as Balarama and Krishna.

Epigraphic Evidence of Krishna Worship

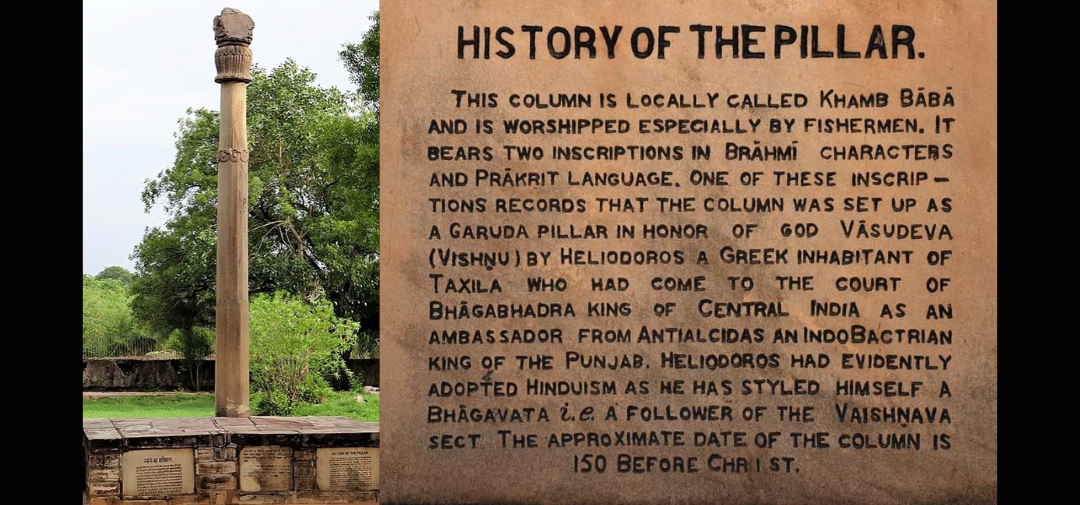

Beyond numismatic and archaeological sources, inscriptions offer compelling proof of Vasudeva Krishna’s widespread veneration. The Besnagar pillar inscription from Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, identifies Heliodorus, a Greek ambassador to the Shunga court, as a "Bhagavata"—an ardent devotee of Vasudeva Krishna. Also known as the Pillar of Heliodorus is thought to symbolize Vasudeva, later recognized as Krishna’s father. Its three distinct sections may represent a cosmic link, uniting the earth, the sky, and the heavens, serving as a bridge between these realms. Similarly, inscriptions from Nagari, Rajasthan, dating to the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, reference temples dedicated to Balarama and Krishna, affirming the deities’ enduring influence.

The Evolution of Balarama’s Worship

Initially, the worship of Balarama was prominent in Mathura, but over time, Vasudeva Krishna eclipsed him. The Mahabhashya of Patanjali (2nd century BCE) references multiple temples dedicated to Balarama, indicating his once-significant role. Texts such as the Arthashastra and various Puranas describe Balarama’s affinity for alcohol and his association with snake worship. The Mahabharata presents him as an avatar of Sheshnaga, reinforcing his divine stature.

One particularly famous legend recounts Balarama’s strength in altering the course of the Yamuna River. Overcome by nostalgia and intoxication, he commands the river to come closer. When it refuses, he forcefully drags it with his plow, a feat immortalized in Hindu tradition.

The Rise of Krishna Bhakti

The worship of Vishnu has undergone significant transformations over centuries. The grammarian Panini (5th–6th century BCE) mentions the Vrishni or Satvata tribe that revered Vasudeva as their supreme deity. The Abhiras, a tribe that migrated to India around the 1st century BCE, similarly venerated Krishna as Gopala, the divine cowherd. The Padma Purana even suggests that Vishnu prophesied his birth among the Abhiras in his eighth incarnation.

While Krishna’s heroic exploits were detailed in ancient texts like the Vishnu Purana and Harivamsha, the concept of Radha—Krishna’s divine consort—did not emerge until the Bhakti movement gained momentum in North India. Radha is conspicuously absent from early texts such as the Bhagavata Purana and Vishnu Purana, only becoming prominent with the 12th-century poet Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, which romanticized her relationship with Krishna.

Significance of Agathocles’ Coins

The coins minted under Agathocles provide invaluable archaeological and numismatic evidence of the widespread influence of the trio of deities beyond Dwarka and Mathura. Their iconography, blending Greek artistic elements with distinctly Indian deities, highlights the deep cultural and religious exchanges between the Indo-Bactrian and Indian worlds. The attire and the figures depicted on the coins are Indian, the head gear and boots bear Greek influence. These coins confirm not only the early worship of Krishna, Balarama and Subhadra but also the extent of their veneration, paralleling later traditions seen in Jagannath Puri, the holy seat of the “Lord of the Universe.”

Furthermore, the bilingual inscriptions in Greek and Brahmi reflect the fluid nature of faith and identity in ancient India. As such, Agathocles’ coinage marks a significant phase in the evolution of Vaishnavism, serving as a tangible link between diverse civilizations and religious traditions. Agathocles' coins, along with the inscriptional evidence uncovered, serve as key pieces in piecing together the rich mosaic of Indo-Greek history. The era's blending of geographies and ideas resulted in an extraordinary flourishing of cultural artefacts, leaving behind a legacy that continues to illuminate the ancient world’s interconnectedness.