Bagh-e Babur, the tomb garden of the founder of the Mughal dynasty, is an important site among Mughal monuments. Years of unrelenting armed conflict and political upheaval left deep scars on the site until it became the focus of a grand restoration project by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

For nearly 150 years, Babur's descendants, particularly Jahangir and Shah Jahan, honored his memory by investing in grand projects to enhance and maintain the garden.

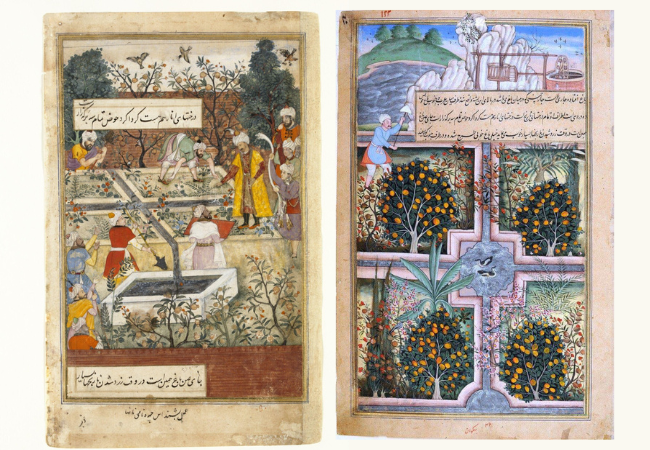

These traditional Mughal gardens are known for their orderly design, featuring geometric layouts and water channels that create distinct sections of the space, a layout referred to as chahar bagh, meaning "four gardens." They often include beautiful water features like channels, fountains, and cascades, along with elegant pavilions and a central axis that offers stunning views. Rich plantings with carefully selected trees, herbs, and flowers enhance the garden's beauty.

The old-Iranian term for these gardens, "pari-daiz," means "earthly paradise," reflecting an ideal of harmony and divine order, bringing together the faithful in the spirit of Islam. The garden’s perimeter walls serve as crucial protective barriers, as described in the Holy Koran.

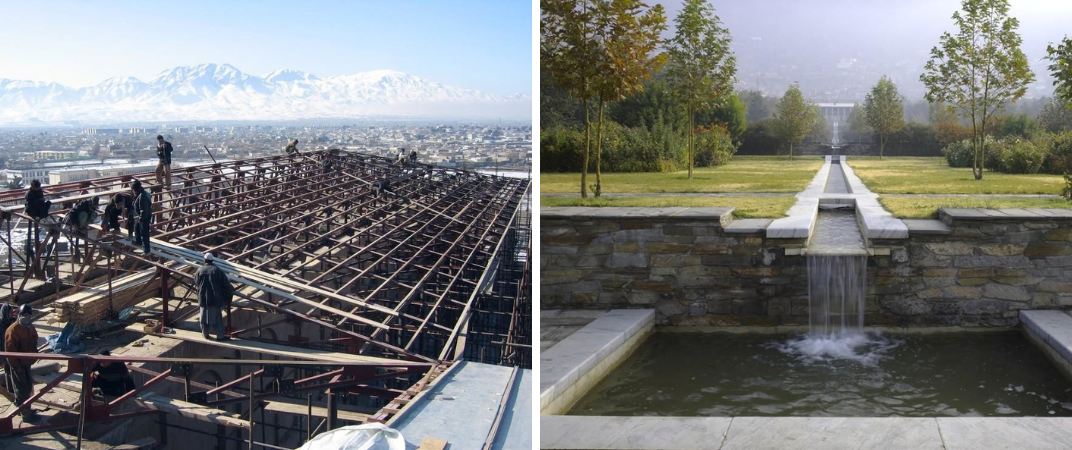

In 2002, a plan was initiated to restore the eleven-hectare garden when the Aga Khan Development Network signed an agreement with the Transitional Afghan Administration. Work began in 2003 to clear remaining unexploded ordnance while focusing on preserving Babur’s grave enclosure, which had changed significantly over time.

The original screen surrounding Babur’s grave, once ravaged by warfare and vandalism in the 20th century, was meticulously rebuilt between 2002 and 2006 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The restoration was guided by a 19th-century drawing by Charles Masson, exemplifying the importance of preserving architectural heritage for future generations. Using marble fragments discovered from the site, the restoration team designed a replica of Babur’s original marble enclosure around his grave.

In 2004, restoration efforts also included re-roofing the mosque built by Shah Jahan in 1675, replacing damaged marble elements, and refurbishing the mihrab wall.

Other historic sites, such as the 19th-century garden pavilion and the Queen’s Palace, have been restored and are now used for public events. Excavations in 2003 uncovered the stone foundations of a 17th-century gateway, leading to the construction of a Caravanserai complex using traditional methods. This complex now houses an interpretation center and various facilities.

The landscaping aimed to restore the garden's original charm by reintroducing flowing water and reshaping the terraces into distinct orchards. Stone pathways and stairs line the central axis, flanked by rows of plane trees and a variety of fruit trees, including pomegranates, apricots, apples, cherries, and peaches. Beyond this main area, the terraces are planted with mulberries, figs, and almonds, along with clusters of walnuts along the newly constructed perimeter walls.